July 1 Now Marked as a Symbol of Resistance, Mourning, and National Awakening

On July 1, 2024, Bangladesh witnessed the beginning of what would become one of the most transformative and turbulent chapters in its political history. What started as a student-led protest demanding reform in the government job quota system escalated into a nationwide uprising that fundamentally altered the nation’s political landscape. Now referred to as the July Uprising, the events that unfolded during those 36 days not only led to the resignation of a long-standing prime minister but also marked the emergence of a new era in the country’s civic and democratic engagement.

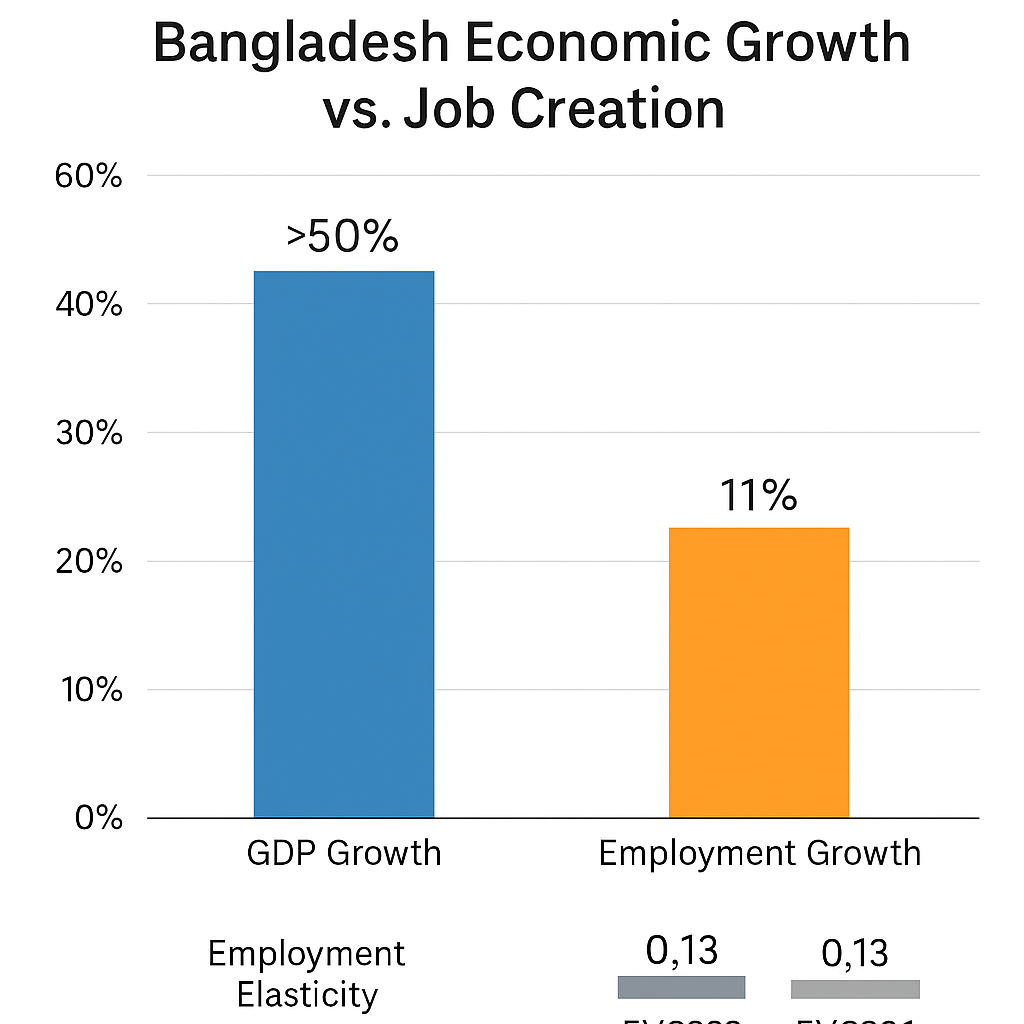

The movement initially emerged from widespread dissatisfaction among university students who had grown increasingly frustrated with what they saw as an unfair and outdated quota system in government recruitment. Years of unaddressed concerns, coupled with rising unemployment and a general disillusionment with state institutions, had created a climate ripe for unrest. On the morning of July 1, thousands of students from major public universities including Dhaka University, Rajshahi University, and Shahjalal University of Science and Technology gathered in protest. Carrying banners and chanting slogans, they demanded immediate and transparent reforms.

The government’s response was swift and severe. Security forces were deployed across major cities, and attempts to disperse the students quickly turned violent. Tear gas, rubber bullets, and, in some instances, live ammunition were used to suppress the demonstrations. One of the first fatalities occurred in Rangpur, where a student named Abu Sayed was shot dead during a clash with police. His death would become a symbol of the movement, sparking national outrage and pushing thousands more to join the protests.

Within hours, what had been a student protest morphed into a broader civilian uprising. Teachers, doctors, garment workers, and even some members of the police force began to express solidarity with the demonstrators. Strikes were called in various sectors. Human chains formed in towns and cities across the country. Social media, though heavily restricted by the government, became a vital tool for organizing and spreading information. Despite attempts to control the narrative through internet shutdowns and censorship, footage of police brutality spread quickly, both domestically and internationally.

As the protests intensified, the government hardened its stance. The demonstrators were labeled as terrorists and enemies of the state. Hundreds were arrested, including student leaders and journalists. News outlets were threatened or shut down, and the state tried to maintain a strict hold on information. Yet the repression only fueled the protesters’ determination. The original demand for quota reform evolved into a larger call for an end to authoritarian governance, systemic corruption, and the erosion of democratic norms.

Dhaka University became the epicenter of the resistance. On multiple nights, violent clashes erupted between students and police on campus grounds. Some university dormitories were raided. Injured students were denied medical care at state-run hospitals. Still, the protestors remained defiant. The image of students holding bloodied flags and makeshift shields became iconic. Civil society organizations, religious leaders, and diaspora communities voiced their support. The United Nations and multiple foreign governments issued statements condemning the use of excessive force and urging the Bangladeshi government to show restraint and begin dialogue.

In a dramatic escalation, the government deployed military units to major protest zones. However, the move backfired. In some instances, soldiers refused to act against unarmed civilians. Reports surfaced of army officers quietly siding with the demonstrators, refusing to carry out orders that they deemed unconstitutional. This internal rift further weakened the government’s control.

By mid-July, the streets of Dhaka were filled daily with tens of thousands of protestors. Key government buildings were surrounded. Public officials began resigning. There were reports of diplomatic personnel quietly leaving the country. With international pressure mounting and domestic control slipping away, the ruling party found itself increasingly isolated. On August 5, 2024, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina formally resigned from her position, ending over a decade of uninterrupted rule.

In the aftermath, a transitional advisory government was formed, led by Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus. Promising to uphold democratic values, ensure justice for those killed during the uprising, and initiate reforms, the new administration quickly declared July 1 as a national day of remembrance. A full investigation into the violence was launched, and efforts began to memorialize those who lost their lives.

Estimates of the death toll vary widely. The official government figure lists 834 fatalities. Independent human rights organizations and international observers suggest the number may be closer to 1,400. A comprehensive citizen-led initiative known as SAD (Students Against Dictatorship) has documented 1,581 confirmed deaths and thousands more injured or disappeared during the unrest.

Today, July 1 is remembered not just as the beginning of a protest, but as the catalyst for a nationwide awakening. For many, it symbolizes the reclaiming of power by ordinary citizens and a resounding rejection of authoritarian rule. Memorials have been erected across the country. Scholarships and institutions bear the names of fallen protesters. And the memory of those 36 days continues to inspire a new generation determined to protect democracy, transparency, and justice in Bangladesh.

source : thedailystar